—it reaches out it reaches out it reaches out it reaches out—

One hundred and thirteen times a second, nothing answers and it reaches out. It is not conscious, though parts of it are. There are structures within it that were once separate organisms; aboriginal, evolved, and complex. It is designed to improvise, to use what is there and then move on.

(Cibola Burn, James S. A. Corey)

Throughout history, cultures have intuited the existence of entities they could not touch or see, but instead understood through the rippling effects and influences throughout the community.

Called tulpas, demons, egregores, tuklus, servitors, golems, djinn, tiki, loa, elementals, phantasms, kami, and many more names as numerous as the personalities of the entities themselves, these entities can broadly be described as thoughtforms.

Each culture and individual person inevitably shapes the understanding and behavior of a thoughtform, with even extreme manifestations like voices heard by schizophrenics acting friendlier in more communal cultures. This difference extends to terms used and the expectations of thoughtforms, Buddhist cultures imagining “tulpas” as helpful friends and guides while Europeans call thoughforms of a similar size and capacity “servitors” and interact with them as mission-driven servants.

This wide variation makes it difficult to capture all possible complexity of thoughtforms in a simple taxonomy, but a few lenses are reliably useful when approaching this study. Looking at the effects, it’s possible to infer benevolence or malevolence from an entity. The structure that gives rise to a thoughtform can also provide insight on its likely goals and manifestations.

As thoughtforms can grow and decay through a life cycle, however, it’s also useful to track their metaphorical size.

The size of a thoughtform can be generally modelled as the total mental energy it represents. A brief, flitting idea across a single mind is nothing more than a thought or an impulse, but an enduring and broadly entrenched egregore commands far more pull in memetic space. As a thoughtform grows, it also develops increased autonomy and can begin to influence those affected by it, in some cases to the extent that they go against their own interests. The number of people touched by a thoughtform, then, is not cleanly linear with the size of the entity. Many people vaguely aware of an idea but not particularly committed to it will not create a strong thoughtform, and one created by them will easily fall to one created by a smaller but hardcore group of zealots.

In the artifacts that are conscious, memories of vanished lives still flicker. Tissues that were changed without dying hold the moment that a boy heard his sister was leaving home. They hold multiplication tables. They hold images of sexuality and violence and beauty. They hold the memories of flesh that no longer exists. They hold metaphors: mitochondria, starfish, Hitler’s-brain-in-a-jar, hell realm. They dream. Structures that were neurons twitch and loop and burn and dream.

(Cibola Burn, James S. A. Corey)

Impulses

The smallest example of a thoughtform is traditionally not thought of one at all. An impulse is a brief, fleeting blip of emotion, held by a single individual and often holding no verbal or linguistic content at all.

These flashes are rarely remembered, much less reflected upon, but they are the etchings in humanity’s soul that allows for the tendrils of larger movements to begin to take hold. Once larger thoughtforms are powerful enough, they can cease riding pre-existing impulses and begin causing them intentionally.

To manage and defend against negative impulses, environmental control is critical. They do not stay for long enough to be consciously caught and observed, so their effects must be analyzed in the micro in much the same way that the largest thoughtforms are tracked in the macro. Their imprints will remain visible. Whether that be the happy glow of a good conversation lasting well past the time it ends or the exhaustion of the pressure caused by mouthing toxic lies while going along to get along, every impulse will leave its subtle fingerprints on the soul it passed through.

Thoughts

When a thoughtform first takes incorporeal shape, it must begin by colonizing a single mind. A thought can be viewed as the smallest truly packaged thoughtform, one that exists in a single mind and is exceedingly temporary.

Not even demanding the individual’s full attention, thoughts can lurk in the background of a mind and nudge behavior without ever being fully recognized. Unlike impulses, thoughts can be conscious or unconscious, but are usually at least somewhat linguistic and structured. Often somatic in origin, thoughts can encompass broader mental patterns that are still limited to a single individual like desires, preferences, and aspirations.

These thoughts are not socially-mediated or shaped by outside forces, however, at least at this stage. Selection has not yet begun its work other than the thought competing with others within the individual.

It reaches out and finds more power. Something fails. Many things fail. Something that was once a woman cries out in silent horror and fear. Something that was once a man prays and names it Armageddon. It reaches out. It narrows only slightly as it reaches out. And at its center, the empty place gains definition. Patterns begin to match, simplifying into lower-energy structures.

(Cibola Burn, James S. A. Corey)

Memes

Once a thoughtform spreads to multiple different minds, it becomes subject to the same aggressive pressures that filter genes in the somatic environment. A meme, then, is the smallest multitudinous thoughtform, and both influences and is influenced by its carriers. While thoughts and impulses are limited to a single person and so any impact is driven only through the power exerted on that individual, depth rather than breadth. Memes, by contrast, can spread a mile wide while remaining only an inch deep, and sometimes entire cultures can become blanketed in minimally-invasive and easily-shed but night-upon-universal memes.

Usually starting with an innovator’s insight, a meme can be an explicit belief or technique such as proverbs or work methods. They also, though, can be emergent from the interactions between individuals, such as an object’s ‘value’ or rituals like handshaking. Sigils, runes, and other more permanent markings are also examples of this size of thoughtform. If there is any ‘power’ embedded in, say, the Seal of Solomon, it seems apparent that most of the effective power of such a symbol comes from the effects it creates in those who interact with it rather than anything inherent to a couple quick strokes of a pen.

Memes are well described in Richard Dawkin’s book The Selfish Gene, but many of the implications of his novel idea are left unexplored. He introduces them without grounding in the broader thoughtform context, as much of that work was yet to be undertaken:

The new soup is the soup of human culture. We need a name for the new replicator, a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation. ‘Mimeme’ comes from a suitable Greek root, but I want a monosyllable that sounds a bit like ‘gene’. I hope my classicist friends will forgive me if I abbreviate mimeme to meme. …

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperm or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.

(The Selfish Gene, p. 192)

There are certain aspects to the meme pool that Dawkins, as a atheist-materialist, was unable to appreciate fully and so did not see the forces influencing and shaping the outcomes beyond simple selection’s work.

The concept of a meme-complex gestures at this possibility, with self-reinforcing packages of interlocking memes like Socratic thought or Schmittian political analysis supporting and reinforcing each other, but the black hole at the center of the meme pool stretches its tendrils far beyond that. As a thoughtform grows in size, it also develops a type of self-awareness and eventually intent. This enables large thoughtforms to heavily favor or suppress certain memes, covering the memetic space with preloaded assumptions that bias the landscape away from competitors, like trees of heaven secreting toxins into the soil to damage other plants.

Tulpas and Servitors

Thoughtform autonomy and size do not directly vary, and tulpas are a relatively small thoughtform that nonetheless carry a fair amount of independence. Hailing from Tibetan Buddhism along with the more commonly known concept of tulkus, tulpas are usually seen as springing from a single mind and rarely long outlasting them. These thoughtforms are still deeply enmeshed in their progenitors, but they have a degree of consciousness and separation from those that created them. A tulpa may interact with only a few individuals, but can be experienced by them as talking and explaining, while a meme may influence billions but only as background noise and tacit assumptions.

Alexandra David-Néel was an explorer and spiritualist, the writer of many early books introducing Tibetan spiritualism to Western audiences. One, Magic and Mystery in Tibet, formed a significant portion of the basis for the first chapter of the book by Mark Stavish that reintroduced the concept of egregores to the modern lexicon, Egregores: The Occult Entities that Watch over Human Destiny.

In Magic and Mystery in Tibet as quoted by Stavish, David-Néel describes the difference between tulpas and tulkus as such:

The Tibetans distinguish between tulkus and tulpas… Tulpas are more or less ephemeral creations which may take different forms; man, animal, tree, rock, etc., at the will of the magician who created them, and behave like the being whose form they happen to have. These tulpas coexist with their creator and can be seen simultaneously with him. In some cases they may survive him, or, during his life, free themselves from his domination and attain a certain independence. The tulku, on the contrary, is the incarnation of a lasting energy directed by an individual with the object of continuing a given kind of activity after his death.

(Egregores, Chapter 1)

Tulpas vary in intent and sophistication, but can largely be understood as variations on imaginary friends. Like servitors in the Chaos Magic tradition, they remain quite simplistic and focused. In fact, practitioners of Chaos Magic often describe servitors as almost automatons, such as Phil Hine in Prime Chaos: Adventures in Chaos Magic:

Servitors can be created to perform a wide range of tasks, from the specific to the general, and may be considered as expert systems which are able to modify themselves to take into account new factors that are likely to arise whilst they are performing their tasks. They can be programmed to work within specific circumstances, or to be operating continually.

(Phil Hine)

The important distinction between thoughtforms like tulpas or servitors and larger ones like tulkus and egregores is that these smaller thoughtforms tend to affect their creators (or hosts) minimally. If they do exert an effect, especially when that effect is malicious, it is usually subtle and slow-acting rather than the immediate reorientation larger thoughtforms can force.

Egregores

A thoughtform changes drastically when it expands past the limits of one mind and becomes a group entity. Viewed as collective delusion, group spirit, zeitgeist, tulku, or egregore depending on the viewer’s beliefs and tradition, these larger thoughtforms can be much more permeable than the smaller and more personal versions. Perhaps understandable as a meme made manifest, egregores move beyond simple influence on people’s thoughts and into the real world.

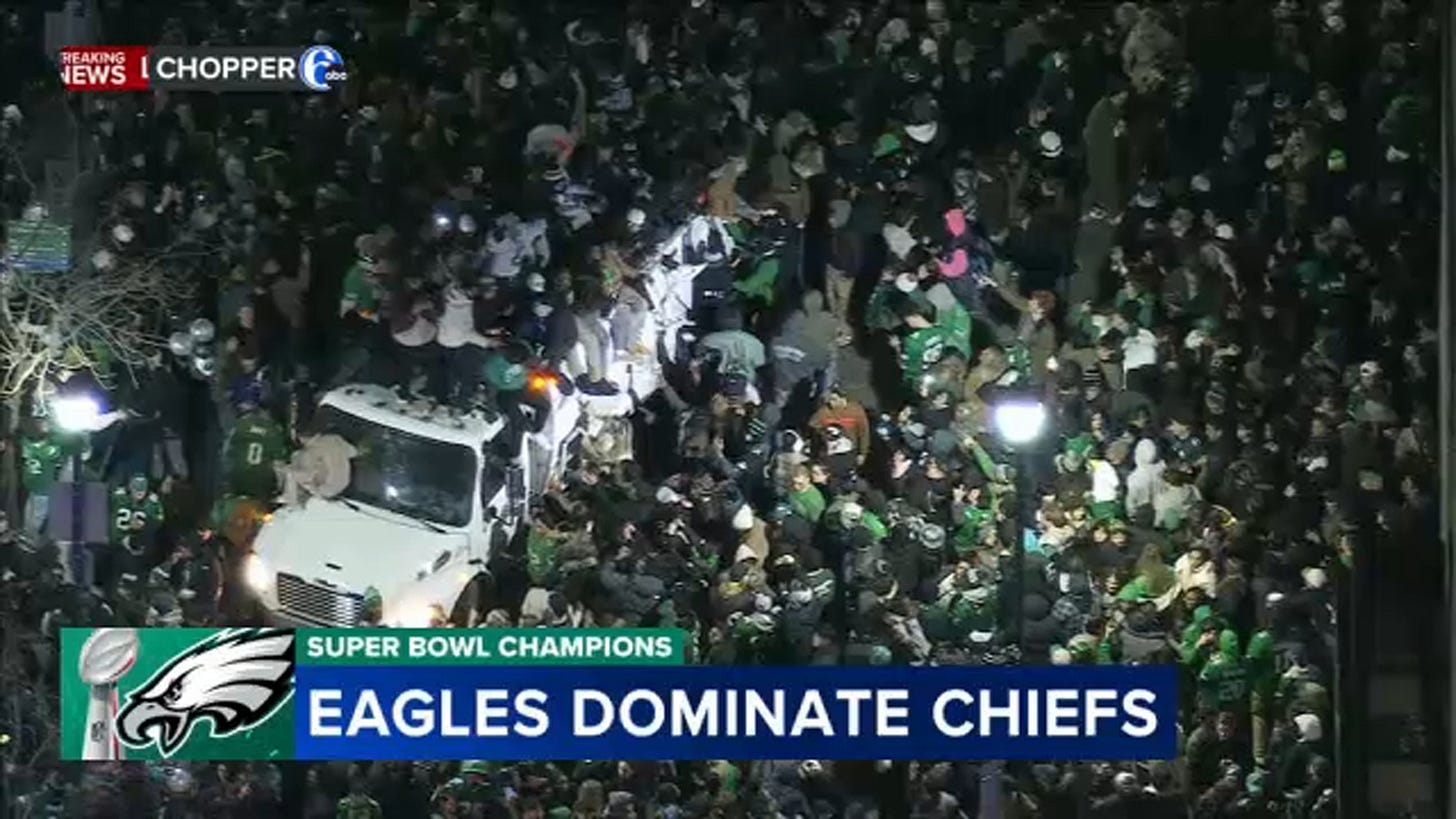

Take for example a sports team. Anyone who has attended a live match is well familiar with the ‘energy of the crowd’ and the home field advantage plays out in each arena. In extreme cases, that spirit of the crowd can result in truly crazy nights, as anyone who lives in Philadelphia can describe:

But on an average working day, an Eagles fan doesn’t necessarily view that identity as primary and is incredibly unlikely to climb traffic light poles. It’s only when the spirit of the crowd picks up the individuals and carries them around, reorienting their subconscious drives towards its ends.

As Gustave Le Bon states in his excellently prescient book The Crowd - A Study of the Popular Mind, written in 1895 and first published in English in 1896:

Crowds, doubtless, are always unconscious, but this very unconsciousness is perhaps one of the secrets of their strength. In the natural world beings exclusively governed by instinct accomplish acts whose marvelous complexity astounds us. Reason is an attribute of humanity of too recent date and still too imperfect to reveal to us the laws of the unconscious, and still more to take its place. The part played by the unconscious in all our acts is immense, and that played by reason very small. The unconscious acts like a force still unknown.

(The Crowd, Gustave Le Bon)

Since egregores arise, emergent, from the individuals that make up its constituent group, their exact boundaries are often fuzzy and they can take on a multitude of forms. Smaller egregores, such as a loose group of friends or even the ‘vibe’ of a restaurant on a particular night, exert little power and tend to be primarily shaped by those participating in its creation rather than driving them from above. A large part of the reasons for this is that there is little mass to subsume into, and all but the most intuitive and impressionable members retain their individuality.

As the group and so the egregore grows, however, people begin thinking, speaking, and acting in “we” terms as their self conception blurs with the group’s spirit. They begin to channel that spirit, but always and forever tainted by their own individual interests and proclivities. This discursive loop, the individual creating, influencing, and then being in turn influenced by the group egregore, lies at the heart of any human-created thoughtform.

The possibility of thoughtforms (perhaps complex entities as a broader term to encompass that which exists apart from humanity) that are not human-derived is an endless topic in itself, but is often presented as more important than it truly is. Depending on one’s religions and occultist persuasions, anything from strict biochemically-derived material explanations to heavenly wars featuring entire swathes of angels and demons may be seen as legitimate explanations.

But in some deeper sense, does it matter if the driving force behind women turning in their sons to be executed is a six dimensional pishacha demon or simple sudden alignment of insanity?

The main objective with studying egregores and other thoughtforms always should be to inform and orient material action, not provide an excuse to avoid difficult changes.

A spiritually-informed but materially-acting individual can avoid the most dangerous effect of an egregore: being subsumed by it. Much as the human mind is vaguely aware of the cells and microbes that make up its body, egregores can be wildly uncaring about the costs they impose on the individuals caught up in them.

One of the best intuition pumps for understanding egregores comes from the science fiction book series and TV show The Expanse. In it, an alien technology called the “protomolecule” is discovered. This material is described by a biological researcher in the first book as “a set of free-floating instructions designed to adapt to and guide other replicating systems”, a sort of nanotechnological bio-computer.

The protomolecule spreads quickly, hijacking whatever biology it comes across and using ionizing radiation as an energy source. Soon, it has taken over swathes of known space, a Baudrillardic mass rolling towards its long-prescribed goals. The consciousnesses it holds are edited and adjusted to serve whatever use the protomolecule has for them, definitely not alive but hard to call dead either:

One hundred thirteen times a second, it reaches out, unaware of the investigator, unaware of the scars and artifacts, the echoes of the dead, the consciousness bound within it. It reaches out because it reaches out. It knows that people are dying in some more physical place, but it is not aware that it knows. It knows that it is constructed from the death of thousands, but it is not aware that it knows. The investigator knows and is aware that it knows.

(Cibola Burn, James S. A. Corey)

This cybernetic analog to the typical cultural-spiritual understanding of egregores demonstrates the dislocations that can be present within these larger thoughtforms. Each component, each individual, may have their own perspective, goals, and information set, but the larger mass may not care or even be aware of that data. Instead, things move in a much more slow and seemingly rule-based manner. Specific predictions are made difficult, and the reasoning behind actions becomes opaque to mere mortals. Instead, those that attempt to sketch out these large thoughtforms often end up resorting to simple but widely-predictive rules that allow for a reasonable amount of play.

Humility is perhaps the most important trait when studying the complex.

Godheads

At the apex of the thoughtform continuum sit godheads, massive beings that in some traditions sit fully outside of time itself.

Esoterica aside, however, godheads can be also viewed as egregores that have reached cultural dominance, ascending to sizes that allow them to leverage other egregores in pursuit of their goals.

Take two modern egregores, Progressivism/Liberalism/Leftism (nothing esoteric is banal enough to limit itself to a single clear name) and Libertarianism. Another name for the first and clearly larger egregore, one that is clearly godhead-tier if any are, might be the Entropic Godhead. This name, like most that point at the true roots rather than the obfuscating marketing material, helps predict some of the seemingly-contradictory elements of the thoughtform like its staunch opposition to space exploration despite the theoretical commitment to Progress.

The Entropic Godhead, then, is driven solely to increase the disorder and chaos in the system and is happy to use whatever tools lie around to do so, even if they happen to be competitive egregores. The Libertarian Egregore, beloved by overly technical engineers and theorycels nationwide, by contrast, would create “freedom” and “liberty”. If it only had the strength to do so, of course.

Thus, from a first-principles analysis, it would make sense for the Entropic Godhead to leverage the principles of “freedom” and the Libertarian Egregore itself when (and only when) those drives create the entropy it is seeking. And that is in fact a consistent strategy, with libertarians trotted out when their summoning bell is rung to dutifully support open borders, drug legalization, and other entropic programs. When they then demand reductions in government spending, firearms freedoms, or deregulation, they are summarily shoved back into their box and told to stuff it until the next time they’re needed to play controlled opposition.

With thoughtforms of this scale, it’s largely impossible to fit a full understanding of even certain components into a single brain, much less the entire entity. Instead, the best engagement strategies seem to involve deliberate and careful engagement with smaller egregores, building up trust networks of individuals and then groups. That way, it’s possible to stress-test the memes, preferences, and egregores of a coherent group, influence it positively, and track its influence more clearly. Then if extrication is necessary, it isn’t required to risk life, livelihood, and all cultural networks to do so.

Complexity is but another name for entropy. That is why the best route to fight decay is to live simply, honestly, and humbly.

This is the most thorough treatment on the subject that I’ve ever read, I believe you have really hit intellectual pay dirt!