The Great Hyperfilter

The Overlapping Looking Glass

When humanity first gained the ability to truly peer into the stars, among the first questions asked was “why are they so empty?”

Advances in glassmaking technology and light reflection techniques led to better telescope lenses, allowing us to see distant planets and their stars with enough detail to determine that none likely held the same complex civilizations that have flourished on Earth. There is a vast expanse of stars, most with their own array of planets at varying distances and orbit times, so from a naïve application of number crunching, Earth should not be all that unique. Even if the conditions that lead to life are relatively rare, they should be common enough in such a massive universe to have allowed for at least a handful of civilizations to leave tracks for us to discover.

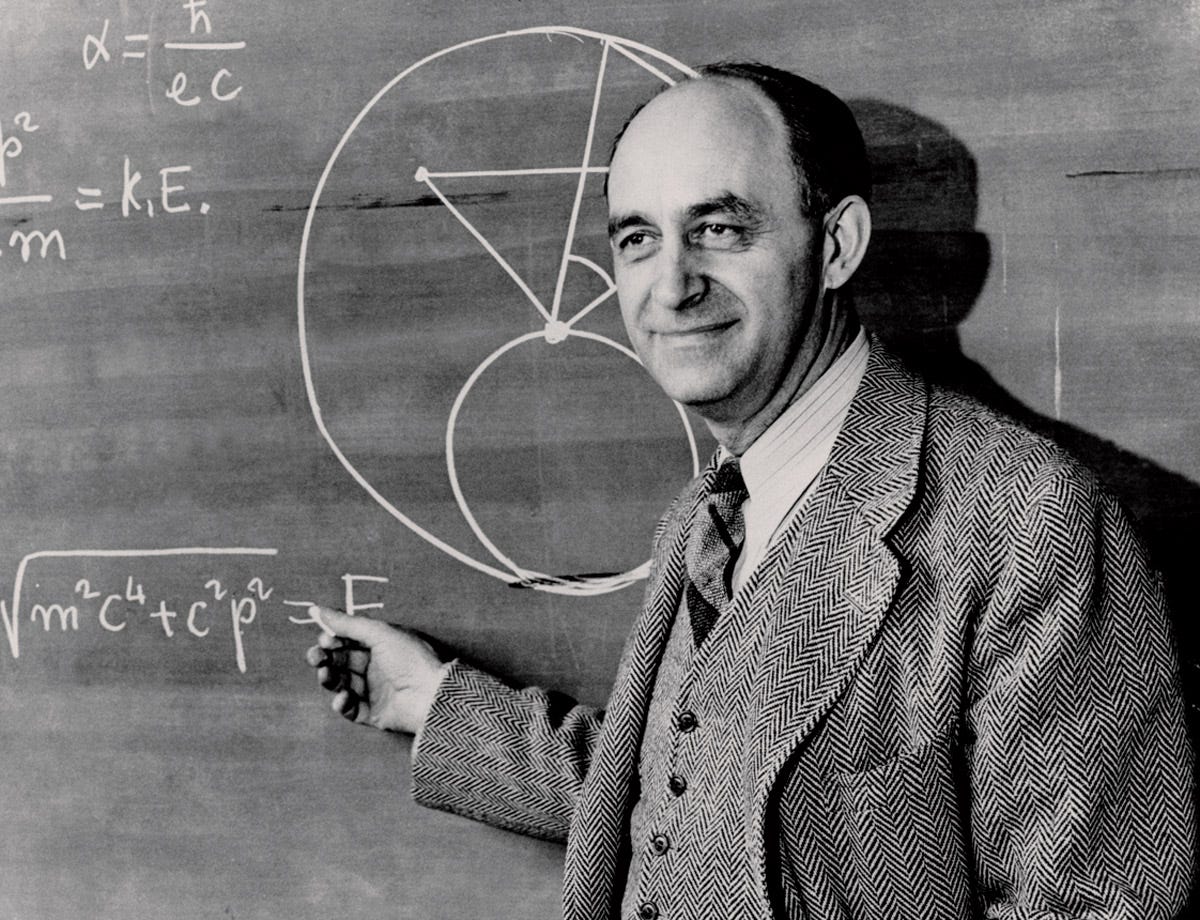

During a 1950 visit to Los Alamos Laboratory, the physicist Enrico Fermi posed another of his notorious “Fermi questions” to his colleagues. Variously recalled by Edward Teller, Emil Konopinski, and Herbert York as “where is everybody?”, “don’t you ever wonder where everybody is?”, or “but where is everybody?”. Following up with a series of calculations on the “probability of earthlike planets, the probability of life given an earth, the probability of humans given life, the likely rise and duration of high technology, and so on”, Fermi showed that Earth should have been visited by extraterrestrials, both ages ago and many times since then.

This problem came to be known as the Fermi Paradox — given the apparently high likelihood of advanced extraterrestrial life, why is there a complete lack of conclusive evidence for it?

Fermi was neither the first to note the paradox, nor the last to suggest solutions to it. Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle referenced the same underlying question back in 1686 in his book, Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, where two characters discuss the probability of Moon beings. Jules Verne included a similar discussion in his 1865 novel Around the Moon. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky also presented the paradox in his 1930s writings, proposing the solution that aliens were deliberately airgapping Earth, hoping that we would develop “a new and wonderful stream of life that will renew and supplement their already perfected life”. This resembles John Ball’s “laboratory hypothesis”, where the Earth is not just passively left alone but subject to active experimentation. Darkest of all is the hypothesis that Liu Cixin popularized as the “dark forest hypothesis”, which proposes that all civilizations look to maximize their share of the total resources available in a finite universe, so civilizations with more advanced technology completely destroy the others as soon as possible after first contact to guard their future.

The simplest material explanation for Earth’s enduring standing as the only planet to host life is that of The Great Filter. Robin Hanson proposed the idea that planets and their civilizations will inevitably run into a selective wall, eliminating all but a lucky few. Though Hansen originally stated the idea through the lens of a single Filter, there does not need to be only one. Assuming all possible life is earthlike, a starting filter is the presence of enough carbon and oxygen in the planet’s atmosphere to create the initial building blocks for life. If that filter is passed, other filters like habitable temperature or the development of sexual reproduction could be rare enough to impose later cullings. Planets that pass the initial tests can still fall prey to potential future filters – maybe they develop simple bacterial life, but once every few centuries or millennia their sun casts off solar flares that sterilize the planet and trap it in a low-complexity loop.

On the planets that do have conditions suitable for life at all, that do move beyond simple bacterial growths to beings capable of complex civilization, the game is still not over. An entirely new class of problems develops, where life can be a threat to itself. Earth is littered with examples of this, so we are able to speak with less speculation about the mechanisms of these filters. Humans have hunted certain animal species to extinction or eliminated them through simple expansionary development. Civilizations have destroyed each other or fallen apart internally through famine, disease, or even their spiritual flame flickering out. These are our best models for what would affect the entirety of complex life on other planets and the endings to their progress.

Some of these endings, and the filters they represent, are not necessarily totally destructive. A civilization does not need to be completely wiped out to have essentially no effect on its planet, and thus even more so its solar system or the universe. The North Sentinelese, who by all living accounts are admirable spear-throwers, are a fully self-sufficient people that have no interest in expansion or conquest and so have never developed beyond basic technologies. They will never shape the world or colonize the stars, so they have not passed their next Great Filter, but that does not mean they cannot last until the Sun goes supernova.

For those of us that do not have the Sentinelese pleasure of complete disconnection from the modern world, we face a different set of problems. Agriculture is conquered (perhaps overly so), calories are abundant. Medicine has advanced to a point where any disease must be simultaneously incredibly virulent and inevitably fatal to threaten the global population, and due to the pressures exerted on diseases as they spread and develop, such a combination is deeply unlikely.

We face smaller problems, but our unique battle is that we must face a mutually reinforcing web of them — the Great Hyperfilter.

Previous civilizations may have experienced some overlap with their filters, but in general problems were faced one at a time, as solutions to one caused new difficulties to arise. Agriculture largely solved the problem of unreliable calories, but at the cost of increased disease pressures from the fetid villages that it enabled. Modern man, however, faces multiple overlapping and interacting filters at the same time, each adding to the difficulty of solving the others.

Our social institutions and truthseeking apparatuses are decaying at precisely the time that the largest mistakes are available stumble over. Productive social norms are disappearing right as societies are aging and losing the vitality to forge new ones. The possibility of irrevocably allocating fatal amounts of resources to projects that produce little more than vapor rises as social institutions and norms that would retain contact with truth are cracking.

It is this Hyperfilter, comprising smaller and simpler tasks that all must be nonetheless solved together, that is our portion of the great voyage.

Artificial Intelligence and Social Institutions

The danger of artificial intelligence is not so much that it creates an unending wave of truthless slop, but more that nobody cares.

Institutional trust is near all time lows, and AI often acts as a simple tool to inflate and distribute the same unreality that was already poisoning our sensemaking institutions. “Grok, is this true?” is unfortunately not a new phenomena, but rather a clarified and memeable version of the same slothful impulse that suffuses our civilization. There is little to no desire to bottom out on ground level reality Truth™, but rather endless appeals to some third party that did the thinking for us, supplying the conclusion in a nice, prepackaged format. Reheat at full power for 1:30, pausing halfway through to stir.

AI is also another ratchet in the trend of social dissolution, further fracturing social bonds by making avoiding their demands and costs easier. It may not have been particularly fun to visit a travel agent to book a family vacation, sit in their waiting room, and end up with a more expensive trip because of their service. That world world where personal interaction was required was by necessity more enmeshed than the one we have now where we can ask ChatGPT for recommendations on the top 5 destinations, have it assist in generating a travel plan, and book the flights online all from the comfort of our comfortable but isolated couch. Travel is not the only area where technology broadly and AI specifically are cultural acid, eating away at already decayed bonds. The employer/employee relationship is also on its last legs, and while the days of tobacco plantations or coal mines relying on little more than destitute human labor are largely over, the post-Industrial Revolution relationship of capital to labor is broken further with AI. Software engineering and other white collar professions were some of the few remaining vocations where the workers and the employer had roughly the same power – Microsoft exists at the scale it does primarily due to disgruntled IBM workers jumping ship, and an incredible number of Silicon Valley startups owe their roots to frustrated or laid-off engineers simply taking their skills to a new venue. With AI, the same gulf that exists in other industries develops and widens – it’s worth less to hire and train a grunt, especially when doing so can give them the freedom to take their new skills to greener pastures.

In a world with a healthy honor culture, CEOs laying off a third of their workforce and replacing them with AI would be seen as a horrific rejection of their responsibility rather than a prudent business move. But because we have been too slothful to maintain the social institutions that built the prosperity we now enjoy, squeezing every additional penny in capital out no matter the social cost is all but required. The nation is filled with employers frustrated at their struggles with finding skilled and reliable labor, only outnumbered by skilled and reliable workers frustrated at not being able to find an opportunity to leverage their skills. Were we to have functional whisper networks, patronage structures, and even properly structured nepotism, we could efficiently pair men with the roles that best align with their skills rather than forcing square pegs into round holes because applying intense pressure is all that the institutions are still good for.

All of this decay and ratcheting difficulty of maintaining social bonds would not be a particularly worrisome problem if our nation had a strong demographic position and developed young men ready to step into their roles, but we have not developed the necessary strengths in our youth for them to fill their role.

Loosened Social Norms and Demographic Collapse

Unfortunately, we do not have a host of cultivated young men ready to take charge. Instead, our nation finds itself in the midst of one of the greatest generational shifts in history. As Baby Boomers depart this mortal coil and leave their unkept estates to anything from their children to Sparky, their favorite corgi, to Carnival Cruise lines by way of purchasing endless tickets to the vapid facsimile of Pleasure Island.

The situation that the youth finds themselves in is the dipole of the Boomer Moment. Instead of functional social institutions ready to be harvested for potential energy, Zoomers and Alphas are starting at the bottom of the energy valley, needing to not only make the difficult individual investments required to restore balance, but to do so in rank defiance of the broader culture. The lust that drove the Boomers along has ossified and faded, with modern analogs standing embarrassed as little more than a ghost dance to a thumos long dead.

We also lust, but only in fits and starts for the temptations of the past that indicated underlying health and vitality. Young men do not lust for the pretty girl that also represents the proto-materials for building family and community, but rather for online pornography and mediated relationships that are doomed to stay forever in digital unreality. Old men lust, but not for positions of authority and the community recognition that comes with the,, but for online gambling winnings and further distractions to avoid grappling with their impending mortality.

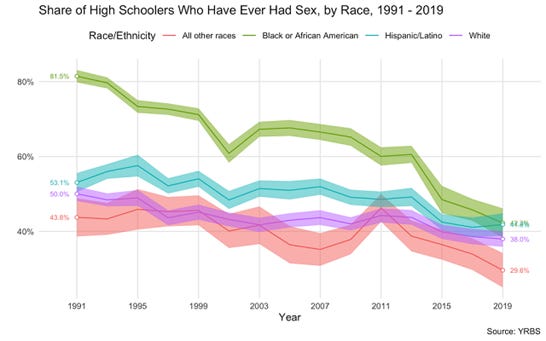

This trend seems to have reached its zenith with the younger generations of Zoomers and Alphas, who are increasingly sexualized but without the underlying sex. While teen adultery is by no means a good metric for a healthy society, the fact that fewer high schoolers than in measured history are not engaging in the classic touchstone for lustful activity is nothing if not odd.

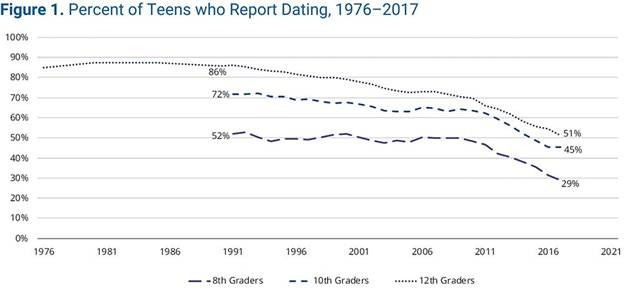

A large part of this shift is likely due to a steep decline in dating more generally. – from a high of almost 90% in the 80s, the percent of 12th graders who reported dating collapsed to 51% by 2017 and has likely degraded from there.

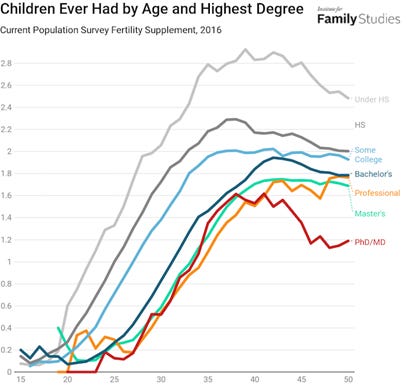

Such trends would seemingly indicate that media and society are becoming cloistered and prudish, but somehow this trend is occurring as the age of earliest exposure to sexual material is pushing ever younger and media is becoming ever more explicit. This sublimation of natural urges into ephemeral soothing techniques quiets our soma, but without the long term value that natural and ancient processes inherently produce. Sex for procreation was too demanding, so society swapped in sex for pleasure. That sex still required two participants, obviously too heady a demand, so now we make peace with solitary pursuits mediated by screens and corporations. The obvious result of this is demographic collapse – the best and brightest are having the fewest children, with even high school graduates struggling to hit replacement.

The problem with the birthrate collapse is not necessarily that there is a smaller teeming mass of humanity to throw thoughtlessly at problems, nor that we need additional biomass to keep the cultural machine greased. The struggle we face is that of the competence crisis, caused by the right people not having children and not passing on their skills and knowledge.

Thus, as resources (especially energy) draw ever more demand, the abilities of precisely those people who are rapidly disappearing will be more critical. An additional set of mutually reinforcing difficulties in the Great Hyperfilter.

Energy Competition

The fundamentals of our modern sensemaking apparatus are breaking down due to AI. The foundations of our skill building — families — are cracking due to flitting distractions and loosened social norms. In this climate comes the greatest demand for logistical and industrial competence the world has yet seen.

“Artificial Intelligence” viewed narrowly through ChatGPT, is little more than a return to the command line — this time with more flexible capabilities drawn out through a process that feels like repeatedly poking a bowl of mushy spaghetti until it vomits the desired output.

“Artificial Intelligence” viewed more holistically, however, represents a possible and likely step change in technology’s capacity and its demands on resource production generally and the electrical grid specifically.

Large Language Models, built on Google’s landmark paper on Transformers that powered this most recent wave of innovation in the space seem to be reaching their peak, albeit a much higher peak than many expected. They can do tasks in minutes that previously took humans days, with the minimal cost of some processing power and a requirement to deeply double check their work. Software engineers are increasingly efficient, with tasks taking minutes that previously took hours. “AI”, while obviously a marketing gimmick that is causing a market bubble, is also an undeniably useful tool and the models powering it have massive capabilities.

They cannot, at this time, however, pilot an autonomous robot and truly supplant human labor.

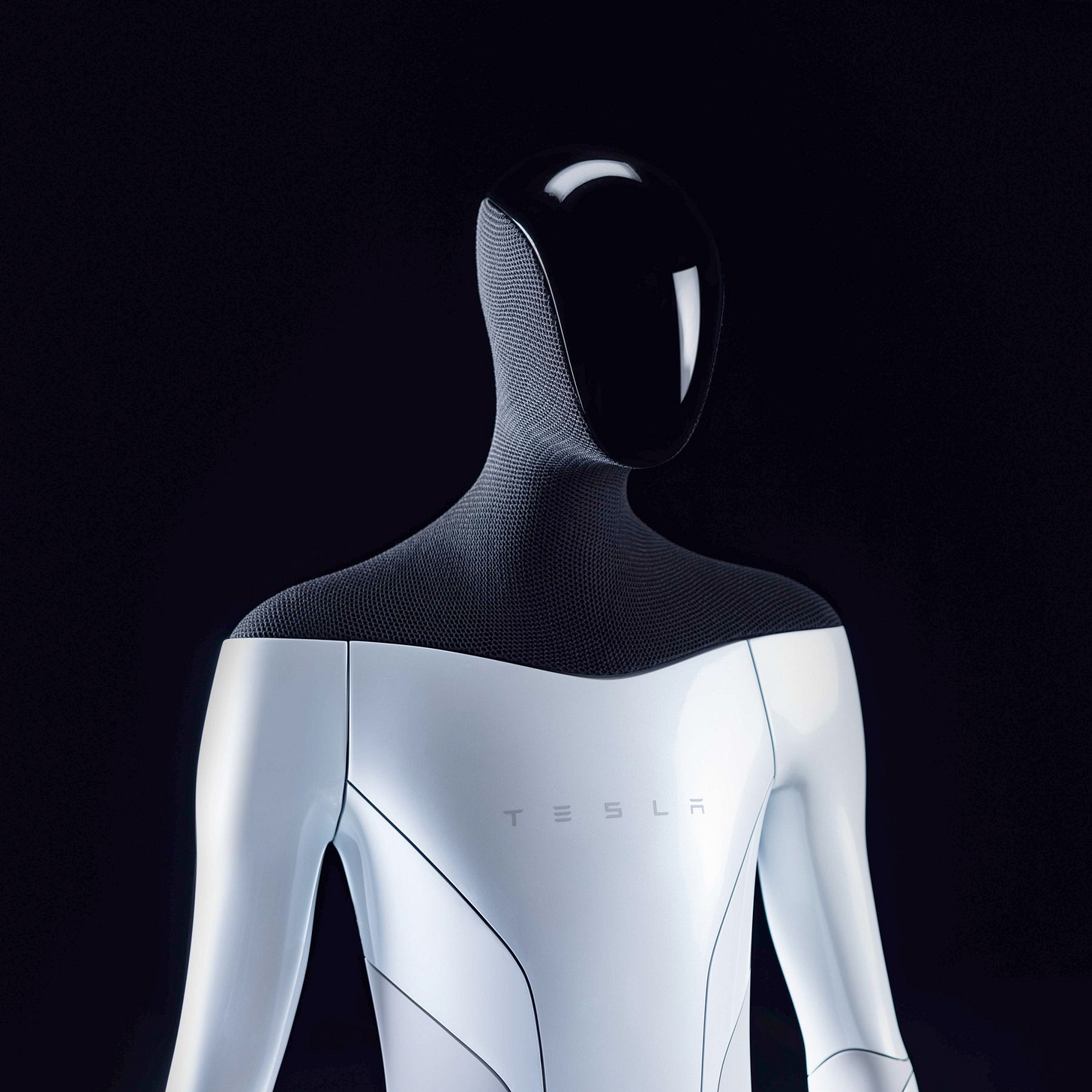

That moment does appear closer than at any time in the past, with companies like Tesla making bold predictions and lofty promises that will likely be fulfilled late and only partially, but a 85% changing of everything delivered two years late still results in societal upheaval.

The resource requirements to facilitate this transition can be analogized to the Industrial Revolution. The life of the average worker became truly unrecognizable in a few generations, with grandfathers growing up peasant agriculturalists and their grandchildren operating newly-invented machines for factories that hadn’t existed, in towns freshly stood up, to serve needs that hadn’t been conceptualized a very short time past.

Our society stands at the precipice of another Industrial Revolution, different than the productivity increases seen throughout recent decades due to the style of transformation expected. Take energy – AI data centers require an increasing share of global energy demand. Some projections lay out the potential for data center energy to account for half of electricity demand growth. If AI capability projections are accurate, this energy growth will spur a wave of industrial productivity as factories bring in mechanized workers and build more efficient processes. Those processes, then, will also require the standup of infrastructure to support such a buildout – humanoid AI workers still require metal and factories. Even in the marketing-spun vision Elon Musk is pushing that results in a $5 trillion market and over one billion humanoid robots by 2050, mines will need to produce metals and factories will require electricity.

The possibility of malinvestment is high, and with our social and sensemaking structures near their all time weakest, the chance that we are dogwalked into a box canyon by effective marketing and unclear fundamentals is a little discussed but dire danger. The malinvestment that is most worrying is not the type that leads to a few quarters of below-trend performance, but something much greater. If humanity were sent back to the dark ages today, the path back to modernity would be intensely more difficult than it was when originally walked. The easiest and richest iron deposits have been mined, the best oil wells have long since been tapped, and even the largest trees have been logged. Portland’s nickname as Stumptown makes some sense when looking around at the relative commonness of trees in the city, but their density pales in comparison to the forests that came before.

If humanity stumbles here, there are no cushions to catch our fall, no handrails to help us back to our feet. This is a potential but underdiscussed Great Filter - civilizations could develop the power to send themselves into a permanent Stone Age, having sawed off the supports on the bridge as they crossed it.

Operation At Scale

The difficulties facing us as AI pollutes the chances of common understanding, social networks slide into disrepair and degrade our ability to coordinate, and titanic demands for resources grow on the horizon would still be a large but addressable worry were it not for the final hurdle – scale.

Human society has become far more enmeshed and integrated than ever before, with supply chains stretching the globe and elite relationships often finding roots more in cosmopolitanism than in a particular care for nation or people. In the worst way possible, where we go one, we go all.

Nuclear weapons are an effective deterrent, but they also magnify the scope of war to an unavoidably planetary scale. Economic warfare, too, is no longer limited to simply cutting off a few key supply relationships, but rather can involve methods as exotic as smuggling in fungal bioweapons to attack the food supply of your enemies, but in doing so possibly endangering the entire globe.

Nation states, too, are far more involved in their citizens’ lives than in ages past, and while the decline and decay of the total state is welcomed by many, the holes they will leave behind as they go will not be easily filled. While the globe-spanning empire may die, the worldwide enmeshment it leaves behind will likely not fully depart – the technology of air travel, internet communications, and so forth will continue to incentivize and enable a level of global perspective that stands outside historic norms. Even if the American Empire disappears, people will likely still be able to vacation in Bali. And when they return home, perhaps with a COVID-like virus, they will spread it just as easily as this last pandemic.

A common and understandable tactic to avoid the pitfalls that lie ahead is divestment, voluntary removal from a position on the game board with the hope that doing so insulates one’s local community from destructive outcomes. And it’s true, some amount of stepping away is both healthy and beneficial. But such self-dispossession also creates deep vulnerability — weaponized fungi targeting food supplies will affect all crops in a given geography, even if some citizens are not supporting their local war machine. Viruses will spread to those living separated lives, such as in 2020 when COVID-19 infected the Amish despite their refusal of air travel and motor vehicles.

The tragedy of scaled operation is that it affects all parties, not just those who choose to participate.

Light on the Horizon

A great adage, true in any age but especially in ours, is that “confusion is opportunity”. Where uncertainty lies, leadership is needed. Where unknowns exist, better information is valued.

Part of the scaled nature of modern society is that problems are too large for one human mind to fully grasp. But we can take the small steps that we know will improve our position.

First, we must live small and live deep. The best strategy when waves are raging is to dive to the bottom of the surf and set up shop there if possible. Globetrotting friend groups will likely splinter and fizzle out, but local relationships with a few good men will become more valuable than ever. As AI improves and spoofing becomes ever more common, physical, in-person interactions will become increasingly needed as a way to build trust and communicate information. This is good, as pretty much all true trust requires sharing foxholes anyways.

Second, we must keep pace with technology but not let it rule us. Knowing how to use Grok is useful and will become ever more critical, but outsourcing our reasoning capacities to manipulated and unreliable AI agents is simply volunteering to be cattle. Artificial Intelligence leveraging “trustless” mechanisms like cryptocurrencies may work to digitally forge trust between asynchronous and distant parties, but if the decades of their existence have proven anything, it’s that rulesets do not make a community.

People do.

Fantastic work, as always, from Cascade Frontier.

Related to the Hyperfilter, or perhaps more in failing to pass the hyperfilter, is there a situation where we could have a soft collapse instead of a hard collapse.

As in, is it possible for things to just gently wind dow in a controlled manner?

Great point on Anthropomorphic Labor Robots. The energy and mining alone for the first generation of them would have to be made by the world's existing global industrial force, which is declining, not to mention that robot production would compete with energy demands for AI and other industries. Also, the AI issue is all hammer and no anvil. Are we potentially throwing vast swaths of first world soceities into precarious limbo just cause?